Larry Fink of Blackrock:

The price of easy money – are the dominoes starting to fall?

Since the financial crisis of 2008, markets were defined by extraordinarily aggressive fiscal and monetary policy. As a result of these policies, we’ve seen inflation move sharply higher to levels not seen since the 1980s. To fight this inflation, the Federal Reserve in the past year has raised rates nearly 500 basis points. This is one price we’re already paying for years of easy money – and was the first domino to drop.

Bond markets were down 15% last year, but it still seemed, as they say in those old Western movies, “quiet, too quiet.” Something else had to give as the fastest pace of rate hikes since the 1980s exposed cracks in the financial system.

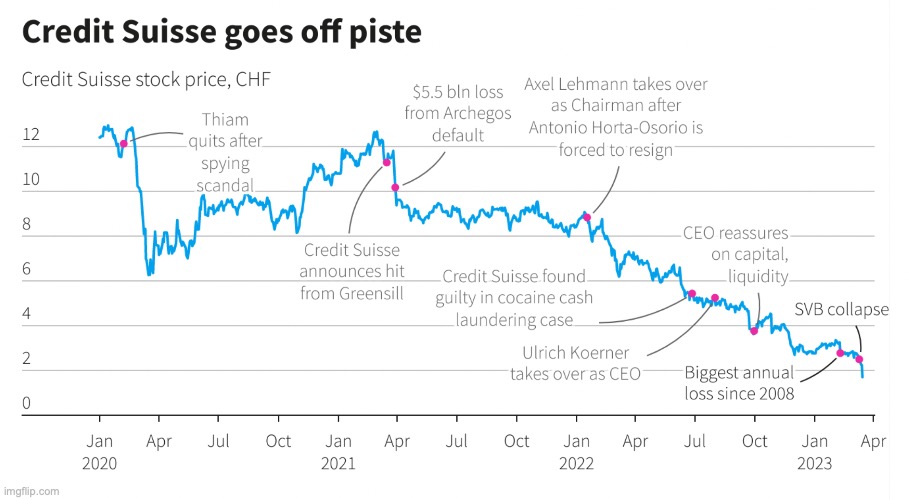

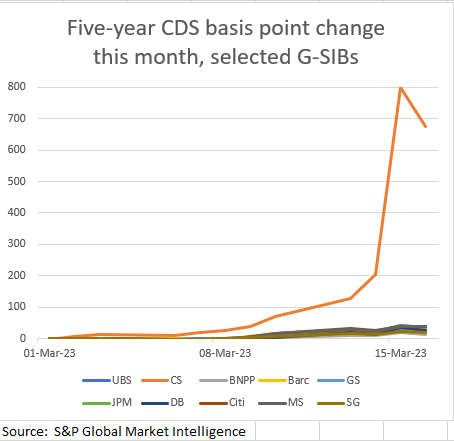

This past week we saw the biggest bank failure in more than 15 years as federal regulators seized Silicon Valley Bank. This is a classic asset-liability mismatch. Two smaller banks failed in the past week as well. It’s too early to know how widespread the damage is. The regulatory response has so far been swift, and decisive actions have helped stave off contagion risks. But markets remain on edge. Will asset-liability mismatches be the second domino to fall?

Prior tightening cycles have often led to spectacular financial flameouts – whether it was the Savings and Loan Crisis that unfolded throughout the eighties and early nineties or the bankruptcy of Orange County, California, in 1994. In the case of the S&L Crisis, it was a “slow rolling crisis” – one that just kept going. It ultimately lasted about a decade and more than a thousand thrifts went under.

We don’t know yet whether the consequences of easy money and regulatory changes will cascade throughout the U.S. regional banking sector (akin to the S&L Crisis) with more seizures and shutdowns coming.

PT 2

It does seem inevitable that some banks will now need to pull back on lending to shore up their balance sheets, and we’re likely to see stricter capital standards for banks.

Over the longer term, today’s banking crisis will place greater importance on the role of capital markets. As banks potentially become more constrained in their lending, or as their clients awaken to these asset-liability mismatches, I anticipate they will likely turn in greater numbers to the capital markets for financing. And I imagine many corporate treasurers are thinking today about having their bank deposits swept nightly to reduce even overnight counterparty risk.

And, there could yet be a third domino to fall. In addition to duration mismatches, we may now also see liquidity mismatches. Years of lower rates had the effect of driving some asset owners to increase their commitments to illiquid investments – trading lower liquidity for higher returns. There’s a risk now of a liquidity mismatch for these asset owners, especially those with leveraged portfolios.

As inflation remains elevated, the Federal Reserve will stay focused on fighting inflation and continue to raise rates. While the financial system is clearly stronger than it was in 2008, the monetary and fiscal tools available to policymakers and regulators to address the current crisis are limited, especially with a divided government in the United States.

With higher interest rates, governments can’t sustain recent levels of fiscal spending and the deficits of previous decades, the U.S. government spent a record $213 billion on interest payments on its debt in the fourth quarter of 2022, up $63 billion from a year earlier. In the U.K., as gilts plunged last fall following the announcement of significant unfunded tax cuts, we saw how swiftly markets react when investors lose faith in their government’s fiscal discipline.

After years of global growth being driven by record high government spending and record low rates. The world now needs the private sector to grow economies and elevate the living standards of people around the globe. We need leaders in both government and corporations to recognize this imperative and work together to unleash the potential of the private sector.